“You Are Shooting (Watching) What you Care”

Day 1 Panel @ Liu Shiming Art Foundation

Moderator: Emann Odufu

Filmmakers: Chelsea Odufu, Maliyamungu Muhande, Autrianna Ward

Official Trailer for Liu Shiming Art Foundation Foundation Film Series “You are Shooting (Watching) What you care”

I’m excited to share that the Liu Shiming Foundation has released the film selections for our first Video Open Call, Everyday Heritage: Cultural Memory in Motion. It was an honor to serve on the judging committee and to witness the range of powerful, inventive works submitted from around the world.

The question we began with was simple: what are cameras paying attention to, and how are artists shaping that attention? Across this two-day screening program, the answers unfold in strikingly different ways—through 16mm grain, handheld movement, archival collage—where “why I care” is embedded into the frame, rhythm, and duration. Here, film is more than documentation or narrative; it becomes a way of directing attention and reorganizing experience.

Under the single thread, You are Shooting (Watching) What You Care, the selected works speak to both artists and audiences alike. I look forward to continuing the conversation by hosting a talk with a group of these filmmakers during the showcase, as we reflect on how moving images carry cultural memory and reshape our everyday heritage.

Liu Shiming Art Foundation releases filmmaker selections for ‘Everyday Memory in Motion’ Opencall

Artist Highlight: Paul Octavious

Date Posted: 8/25/25

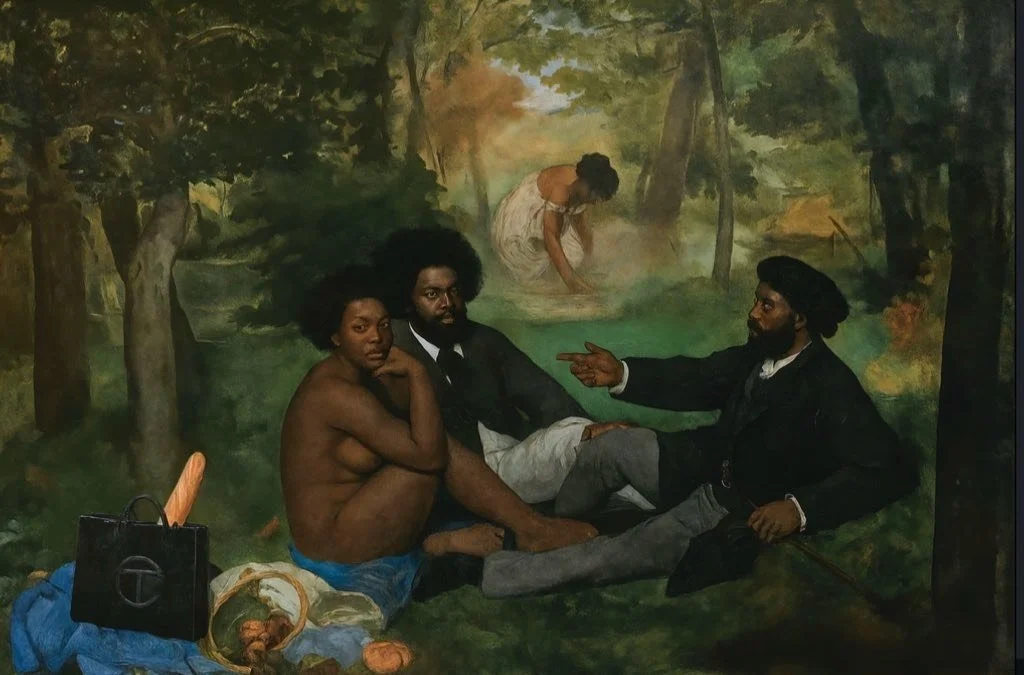

Paul Octavious is a Chicago-based artist and creative director whose work often explores the intersections of culture, history, and contemporary identity. In his ongoing series reimagining master paintings, Octavious reconfigures familiar images to center Black figures and narratives that were historically absent from the canon. He also introduces symbols of modern life, such as the iconic Telfar bag, weaving contemporary culture into the fabric of art history. His remix of Édouard Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass becomes more than homage—it is a meditation on absence and presence, and a dialogue across time about who is remembered and how legacies are made.

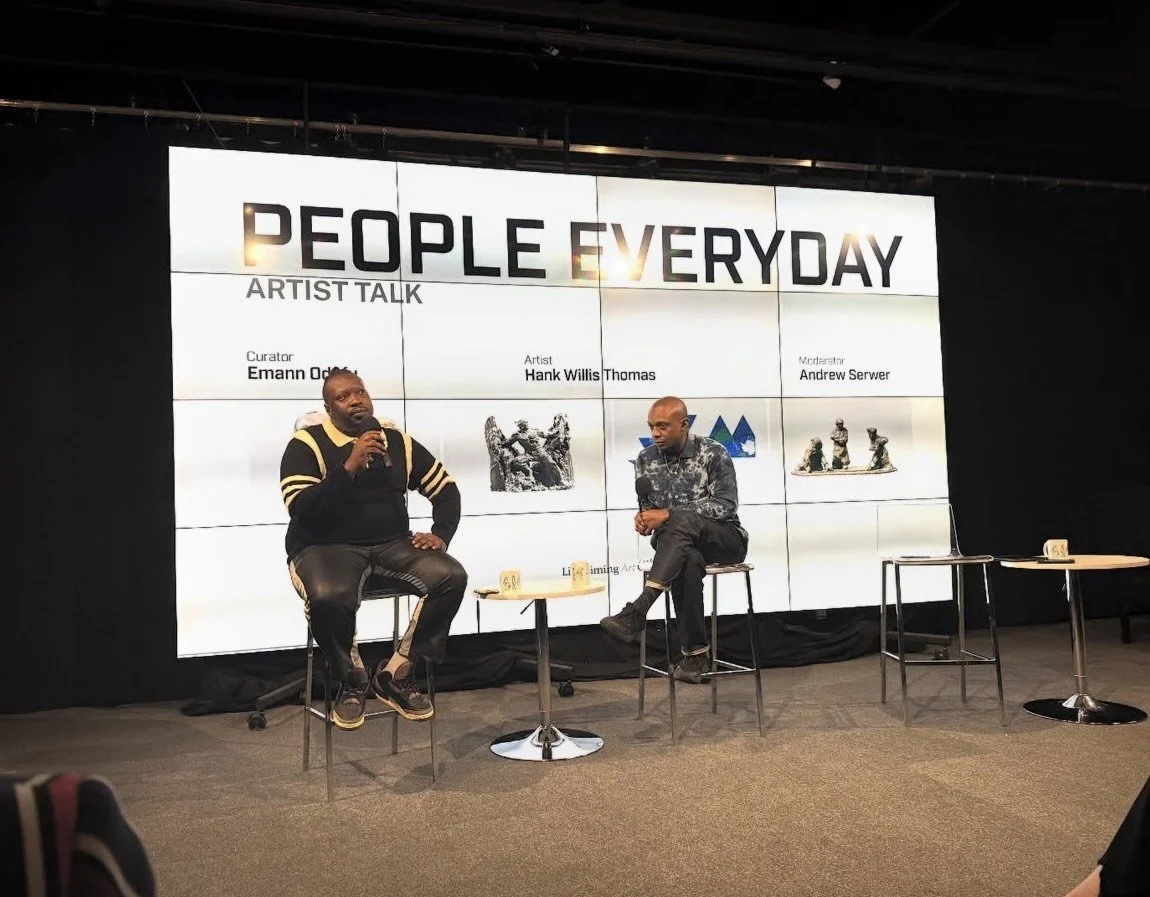

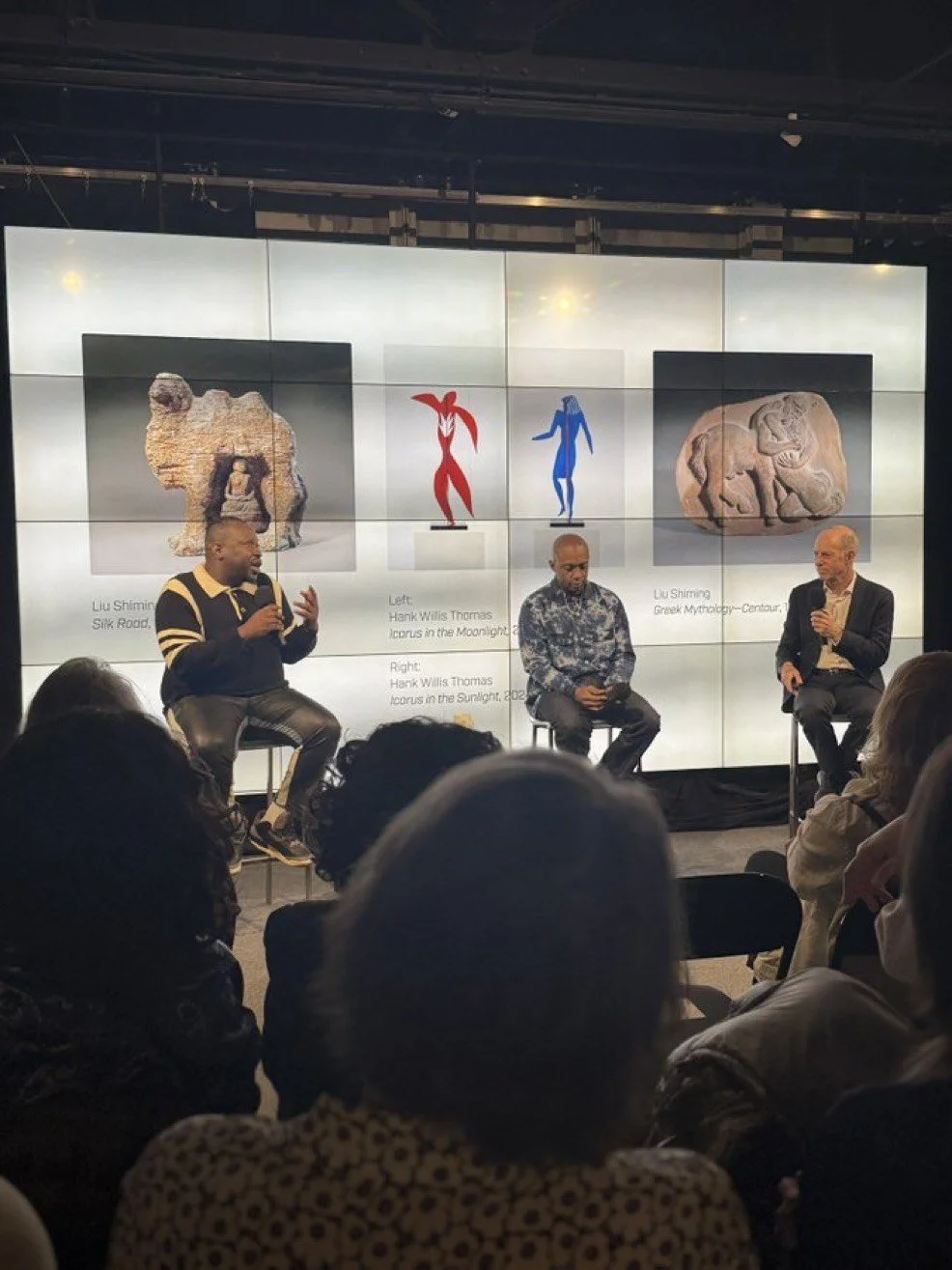

People Everyday Artist Talk @ the Liu Shiming Art Foundation

Date Posted: 8/18/25

I was excited to take part in an artist talk with Hank Willis Thomas at the Liu Shiming Art Foundation, held in conjunction with People Everyday, the exhibition I curated featuring Hank and Liu Shiming. Moderated by Andy Serwer of Barron’s, the conversation was a powerful exchange about art, identity, and the stories of everyday people. It was energizing to see the dialogue between Hank’s conceptual work and Liu’s sculptural practice come alive in front of an audience. I left the evening feeling inspired and grateful for the chance to share in such a dynamic moment of cross-cultural conversation.

Oda Jaune “Miss Understand” Performance Art Film

Date Posted: 12/16/24

Office Magazine x Templon Gallery

Released online: 3/15/24

Directed by Liv Solomon

Performance by Claudia Hilda

Audio by Oda Jaune

As a part of the interview I did with Oda Jaune for Office Magazine on the occasion of her exhibition Miss Understand at Templon Gallery in NYC, we decided to record the performance art piece that was a part of the show and that took place on the last day of the exhibition.

Interview w/ Nancy Baker Cahill for Right Click Radio

Date Posted: 12/7/24

Nancy Baker Cahill is an LA-based, new media artist whose work examines systemic power, selfhood, and embodied consciousness through drawing and shared immersive space. Working at the intersection of art, social impact, and XR, she has developed an innovative and rigorous art practice that invites its audience to imagine more inclusive and sustainable ecosystems. In this interview, the artist discusses her inspirations and aspirations for digital art, blockchain, and NFTs.

Episode Summary: Emann Odufu speaks to Nancy Baker Cahill about how the blockchain can help turn public art into a new caring economy.

Cento

Animated AR Installation

Whitney Museum, 2023

Mushroom Cloud

Animated AR Installation

2021

Whether they Like it or Not

Installation

2024

“First Thought Best Thought” at the National Academy of Design

Date Posted: 11/16/2024

On July 31, 2024 I had the ultimate pleasure of being invited to take part in “First Thought Best Thought” at the National Academy of Design. It was a competition for art critics where your ability to spontaneously come up with critiques of works from the National Academy’s 191st Annual Showcase of works by National Academicians, was put to the test. Needless to say I was nervous, but was esteemed to be on stage with some of the renouned art critics that I was, The competition was based off an idea by Alan Ginsberg on the superiority of spontaneous thought.

Install Shot of National Academy of Designs 191st Annual

The winner of First Thought Best Thought accepting her award.

Install Shot of National Academy of Design’s 191st Annual

Install Shot of National Academy of Design’s 191st Annual

Install Shot of National Academy of Designs 191st Annual

Unbranded: Reflections on Race in the Advertising Industry w/ Hank Willis Thomas

Date Posted: 11/08/24

In March of 2023 I organized a talk with visual artist Hank Willis Thomas at FCB NY where the artist talked about the role advertising has played in his practice, specifically talking about his “Unbranded series” and how it challenges us to look at the images we put fourth as advertisers, artists and image makers, a lot more closely. As part of this talk I curated a selection of 4 works to be installed in the office for 2 months. This talk was the inaugural installment of an Artistic Innovation series that began at FCB NY.

Curator’s Statement:

Unbranded: Reflections of Race in the Advertising Industry, a presentation of four works from Hank Willis Thomas’s Unbranded series explores the evolution of race relations from the Civil Rights Movement to today, as reflected in advertising. Through his lens, Thomas chronicles moments of social progress and instances that, in retrospect, challenge our understanding of equity and representation.

Displayed in the FCB NY office, these works illuminate the duality of advertising’s role in shaping and reflecting culture. On one hand, the images in the office suggest the possibility of a "post-racial" America, yet on closer inspection, they reveal underlying tensions that persist. This is perhaps most poignantly captured in the image entirled Welcome to Full Contact Culture,

Every so often, a moment like Kendall Jenner’s Pepsi commercial reignites critical conversations about culture, authenticity, appropriation, and the social impact of media. These conversations challenge us to reconsider the role of advertising in shaping societal norms and highlight the urgent need to build a more equitable and authentic social ecosystem. Through this series, Thomas invites us to reflect on how far we’ve come—and how far we still have to go.

Flier for the talk at FCB NY

Hank WIlls Thomas chatting with FCB NY CEO and CCO’s

Emann Odufu introducing Hank Willis Thomas at FCB NY

Membership has its Privileges 2006/2008, 2008

Digital C-print, Ed. 1/5

36 x 28 5/8 in. (91.4 x 72.6 cm)

Hank Willis Thomas on stage with FCB NY’s CCO’s (2023)

The Mandingo of Sandwiches 1977/2007, 2007

Lambda photograph, Ed. 1/5

36 x 34 3/4 in. (91.4 x 88.5 cm)

We Are On Our Way 1970/2008, 2008

Digital C-print, Ed. 1/5

33 3/8 x 30 in. (84.9 x 76.2 cm

Hank Willis Thomas Unbranded works being installed at FCB NY.

Welcome to Full Contact Culture 2007/2008, 2008

Digital C-print, Ed. 1/5

36 x 26 in. (91.4 x 66 cm)

Emann Odufu and Hank Willis Thomas

Anselm Reyle: Rainbow in The Dark Exhibition” Art Film (MoCA CT)

Vendor: Tanner & Holmes

Directed by John Tanner

Released to promote the solo show of Anselm Reyle at MoCA Connecticut in 2023 called “Rainbow In the Dark” curated by myself.

Mentalverse- Interview with Jason Boyd Kinsella

Date Posted 11/06/24

Install shot of “Mentalverse” at Perrotin Dubai

For its grand opening in Dubai, Perrotin partnered with ICD Brookfield Place to present the inaugural exhibition of Jason Boyd Kinsella in the Emirates. Titled Mentalverse, the exhibition delves into Kinsella’s ongoing exploration of personal identity and its contrasting manifestations in two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) spaces.

Kinsella conceptualizes 2D as a metaphor for the digital realm—social media, avatars, and curated online personas—while 3D embodies the tangible, multifaceted nature of the physical world. His psychological portraits are meticulously constructed using "building blocks" of personality traits, a creative process inspired by his fascination with the Myers-Briggs personality test.

By juxtaposing 2D portraits with 3D sculptures, Mentalverse invites viewers to reflect on the interplay between these realms. Is there fluidity between the digital and physical selves, or do they remain distinct? Through this exploration, Kinsella provokes a dialogue about the merging boundaries of identity in a society increasingly shaped by the convergence of the digital and physical worlds.

Interview:

EO: Reading about you in preparation for this interview, the term that repeatedly comes about is psychological portraiture. Can you expand on the importance of speaking toward the psyche or personality of your subjects and how or why you think this type of representation is so essential in this digital age?

JBK: To me, it's very easy for people to hide behind personas they curate in the digital space. In today's digital world, people are literally or figuratively creating masks. They are creating these personas that may not be genuine, as you see in social media very often. Everything is exceptionally curated. My work is stripping that away and getting to what I feel are these sorts of iconic representations of the subject's personality. The subjects are people I know personally.

Fundamentally, this is a way of confusing the Myers-Brigg test. This test is built on binaries. For example, you are very feeling, or you are very logical. You are either this, or you are that. By answering a bunch of questions about people, you get down to the essence of what a person is all made of. That's what these building blocks are. It's a psychological framework of the self, and then we fill that framework with our life experiences, our education, how we grow up, etc. That fills it with color and supplies it with life. I'm interested in how these things come together. For me, my work creates a very good representation of how someone is or could be versus how they portray themselves to the world or how we perceive them.

EO: I agree with that. Our culture is very focused on the surface, so it's almost a breath of fresh air to see someone approach things from a psychological or even spiritual vantage point. I personally ascribe to the belief that we are spiritual beings in a physical body.

JBK: To build on what you're saying. In the context of our culture, what we see on the digital is a two-dimensional representation of a person. At present, a significant portion of our life is spent on the phone or zoom. So, it's in the two-dimensional that we are increasingly experiencing and communicating with people, in some cases that we've never met before in the physical.

The reason for me juxtaposing the two-dimensional painting with the three-dimensional sculpture is to challenge how people view themselves and their own perception of how they experience people. The two-dimensional relates to how we encounter people on social media or digital spaces, on a phone, laptop, or zoom. You may never meet people that you interact with. I'm focused on how that experience in the two-dimensional space differs from the physical and three-dimensional space. In 3D, you can see someone more holistically. You can walk around them and see the nuances of their character and what makes them who they are. I want to challenge people with that idea and ask if there is fluidity between the digital, two-dimensional, and three-dimensional, or if there is a clear distinction between the two mediums.

EO: One thing that is very apparent is that you think a lot about the digital.

JBK: I do. The line between digital and physical is becoming more and more merged or blurred. So, the digital and physical fusion is very important to me. We live in a world of avatars and icons. It plays into the way people see themselves. Some people use filters or things of that sort, and it's great they can be creative with their own persona. My work can seem strange to some people, but anyone can form an affinity for it because it deals with our world and the technological tools we all use. To be as relevant as possible is very important to me. Ultimately, there is a familiarity when people see my work, whether painting, sculpture or digital. I work in the digital and think about the digital because I want to make work that people can relate to.

EO: Both of us have one thing in common. I currently work in advertising as a producer. I read that you had an illustrious career in advertising, which interests me. How do you think your background in advertising has served you as a fine artist?

Specifically, I'd like to know if there is a connection between your interest in the human psyche and your background in advertising. To me, advertising is all about understanding and capitalizing on human nature. Ads are a lot deeper than ads. Is this part of your curiosity with capturing the essence and personality of your subjects?

JBK: A big part of my understanding of creation comes from my advertising background. Whether in art or advertising, it's imperative to be culturally relevant. You must reflect the qualities of the world we live in. So, because of that, there is a common ground between advertising and my creations as an artist. Also, the same digital tools I use in advertising are what I'm using as an artist. My work often starts with a sketch, and then I'll bring it into the digital throughout the process, bringing the work back and forth between the digital and physical. There's more of a blend now and less of a distinction between the tools you use in creating physical and digital artwork.

EO: I continually think about the hybridity of different creative realms. To me, everything is starting to become one. Do you see yourself existing between creative realms? Maybe because of your background in advertising, collaborating with brands as a fine artist, making furniture, or helping to design buildings, for example. I'm also curious if you'd ever pursue creating digital art, video, or NFTs or if you are firmly grounded in the physical at the moment. Is there room for more collaboration and creative exploration in your practice?

JBK: It's hard to predict the future. Everything for me must pass this internal test. It has to be genuine and feel real to me. Right now, I'm focusing on what I'm currently doing. A lot of people are asking me if I want to make NFTs. And for me, I don't really feel like I'm there yet. I don't feel the need to explore that as yet. All those kinds of things, whether medium or collaborating with brands, have to feel natural; if it works well for me in the future, then I'll lean into it. Right now, I'm focused on continuing to build my visual language. So right now, I'm not collaborating with any brands or working with NFTs or anything like that. Everything I'm working on currently is a natural evolution of my creative process, and I'm really focused on sharpening my tools and getting people to see and understand my artwork and visual language

EO: The reason I asked that is when I look at your sculptures especially, I see the potential to scale the "building blocks' larger and to create specifically in the architecture or interior design realm or for you to experiment with digital sculpture in virtual reality.

JBK: What's interesting here is that in this exhibition, because it's in an open space at ICD Brookfield, I was asked to design the walls on which the paintings are displayed. So, it was interesting creating from that vantage point. I'm really interested in volume and space. If you look at my painting or sculptural work, you get a sense of that. I live in Scandinavia, and Scandinavia has genuine love and affinity for architecture and furniture design. I collect furniture. Those things are very inspiring to me. It doesn't matter whether it's architecture, design, or even music. I find inspiration everywhere. So, if you look at my work and see a connection to architecture, then great. Especially in terms of the sculpture, it's about being able to walk around and experience my work from a multitude of vantage points. It's about the subjects' personality, of course, but it's really about having that ability to explore for yourself. As far as digital sculptures it's something that I find very fascinating.

EO: Can you tell us a bit about your process of creation? It's interesting to me because you are blending the digital with more traditional artistic creation processes.

JBK: Usually, I take the tools that I learned from the analog world or in the studio and the traditional elements of how to communicate through art. I take those qualities and blend them with the digital. I'm constantly going back from the analog to the digital and the digital back o the analog in my creation process. Everything begins with a sketch on paper. Tons and tons of sketches with a pencil on paper. When I feel it's something I'm excited about and want to explore further in a painting format, I'll take a picture of my sketch and bring it into the computer. I'll explore that with color and volume and then create a painting from that. Then I'll take it back into the digital space from painting and imagine how that translates from the two-dimensional experience into the more holistic three-dimensional experience with my sculpture. So, it's a back-and-forth process, and I'm constantly putting the work through these cycles. To me, it feels like a representation of how we live. We live in this weird seamless world that merges the analog and digital. Sometimes you can't even notice the difference between the two.

EO: Yea, especially as we get deeper into existing within the metaverse or mentalverse, as you may call it.

JBK: Yeah, and the reason for this is to emphasize and challenge people to think about the two-dimensional space and the way we communicate and experience in that space versus the three-dimensional space and how we experience in that realm.

EO: I read that you are a fan of jazz music, and to me, there is a musical quality to your work. I'm curious about what you were listening to when creating this body of work, and do you think it influenced what you created, even if just psychologically?

JBK: Music is great to draw to. I listen to a lot of jazz, but I don't only listen to jazz. I gravitate to jazz in the studio because free-form jazz doesn't call for physical patterns and challenges you in your mind to explore and riff on things in different ways. I love Miles Davis, and his music is amazing. Listening to it, he'll start in one space and move you to another space you didn't see coming, and it challenges you to see things in a new light. Literally, it's like getting a massage in your brain when you really sit with his music and let it sink in.

EO: I was amazed to read that you posted your first artwork on Instagram a little over two years ago and have received a very strong response from the art world. Firstly, do you have any advice for late bloomers from an art world perspective or who have pursued other things but want to be an artist?

JBK: If I could offer any advice to anyone, whether it's an artist or someone who just feels called to a purpose. One thing is that you don't need to just throw everything aside and grind headfirst into it. Instead, you can find a way to move into it in a natural and not reckless way that feels that the universe is rewarding you.

EO: I definitely value that advice and think many people will also.

JBK: It hasn't been a straight path for me. I hope some people can feel like it's never too late to go for it. Also, you must be fearless once you decide to go for it.

EO: How do you deal with your success, and how do you hope to maintain it over what will hopefully be an extremely long and fruitful career? I'm talking more from a holistic perspective.

JBK: I just really focus on the work. There's a lot of noise—a lot of distractions. As I said earlier, I live in Scandinavia. When I'm creating, I go into a vacuum and don't leave it until I have work to show. Then, once I show that work, I go back to the vacuum and start the process again. I like that. That keeps me insulated from the noise and focused on the work, and that's how I'm able to do what I do.

EO: So, this show is in Dubai. Why were you open to showcasing your work here? What makes this an ideal location for you to share your creativity?

JBK: First, the opportunity to show next to Takashi Murakami was a big selling point. To me, nothing beats that. Aside from that, I'm always interested in showing my work with people from everywhere and allowing people to enjoy it. It doesn't matter what city, country, or whatever, if people can experience and relate to it. That's what it's all about.

Berner, 2022

Oil on Canvas

72 13/16 × 61 1/16 inches

Installation View of “Mentalverse” at Perrotin Dubai

Ellen (pairing), 2022

Painting: Oil on canvas / Sculpture: Polystone, aluminium and mix media with paint

Painting : 185 × 115 cm | 72 13/16 × 45 1/4 inches

Sculpture : 200 × 95 × 87 cm | 78 3/4 × 37 3/8 × 34 1/4 inches

Leo, 2022

Acrylic and oil on canvas

72 13/16 × 61 1/16 inches

Emann Odufu with Jason Boyd Kinsella at the opening of “Mentalverse” at Perrotin Dubai (2022)